Hotline: +381 61 63 84 071

Study exposes deeply entrenched victim-blaming and systemic silence on digital violence in Serbia

Photo: Source N1

There is no official data on the prevalence of digital violence in Serbia, but experts agree that it is on the rise. Alongside children and young people, the most frequent victims are girls and women under the age of 30. Particularly alarming is the fact that the vast majority of them perceive themselves as responsible for the violence they have experienced.

Jelena Hrnjak, Program Manager at the NGO Atina, told the N1 portal that every second woman in Serbia experiences some form of digital violence before the age of 30. Research on digital violence against women and girls in Serbia, conducted by Atina with the support of UN Women, shows that one quarter of respondents report having experienced digital violence, with women being disproportionately affected.

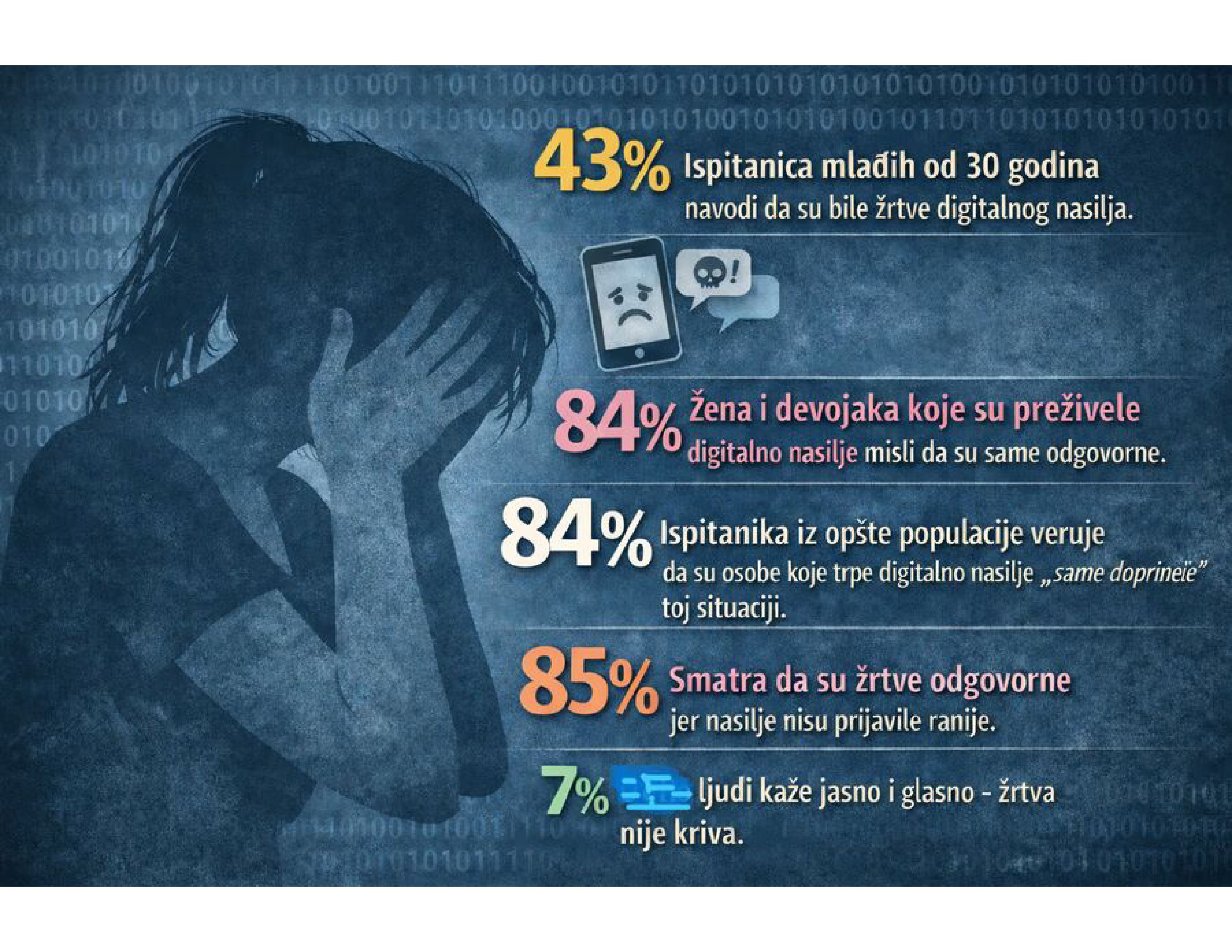

“Young women are the most vulnerable: as many as 43 percent of respondents under the age of 30 say they have been victims of digital violence. At the same time, we see a specific risk among women aged 30 to 45, particularly in intimate partner relationships, where they are disproportionately exposed to digital control and restrictions on their online activities imposed by partners. In intimate relationships, digital violence is an extension of control and abuse,” Hrnjak warns.

What is especially alarming in the research “Ne lajkul nasilje” is the finding that 84 percent of women and girls who survived digital violence believe they themselves are responsible for what happened to them.

Slađana Đorđević, a psychotherapist specializing in trauma work, explains to N1 that girls and women who experience digital violence often tend to internalize a sense of responsibility. This process is particularly seen among young girls.

“Among young girls, the sense of identity is still developing, and with it boundaries and a sense of responsibility. Adolescents’ self-confidence and self-esteem are still forming, so they are more likely to question themselves rather than the perpetrator (‘something must be wrong with me’ or ‘I must have done something wrong’),” the psychotherapist explains.

It starts gradually, almost imperceptibly, and escalates into open abuse.

She warns that digital violence, precisely because it occurs in the virtual space, further blurs boundaries.

“Very often this type of violence begins gradually, almost imperceptibly, and the person slowly becomes accustomed to that manner of communication. Over time, however, it escalates into open insults and humiliation, at a point when the woman has already begun to question herself and her boundaries,” Đorđević adds.

While the fact that many victims blame themselves is concerning, what is even more troubling is that their social environment often shares the same belief. Atina’s research shows that 84 percent of respondents from the general population believe that people who experience digital violence have ‘contributed to it themselves.’ In comparison, 85 percent believe victims are responsible because they did not report the violence earlier.

The victim is not to blame

How few people in Serbia unequivocally stand in defense of victims is illustrated by another finding from Atina’s research: only seven percent of respondents clearly and openly state that the victim is not to blame.

Hrnjak told N1 that the research revealed a painful but essential truth: Serbia continues to be dominated by a culture that shifts responsibility for violence onto victims.

“This is not a reflection of their character, but of the environment we live in. For years, women have been exposed to messages that they ‘provoked it,’ that they ‘were not careful enough,’ or that they ‘should stay silent so things don’t get worse.’ In such an environment, it is not surprising that women begin to believe they are to blame, even though we know that responsibility lies exclusively with the perpetrators, and with institutions and society that should protect them,” she said.

Psychotherapist Slađana Đorđević also warns that we live in a society where narratives that place responsibility on women are widespread.

“Statements such as ‘she asked for it,’ ‘look at the photos she posts,’ or ‘she is provocative’ are common. When these attitudes are combined with gaslighting by online abusers, who often claim they were ‘provoked,’ it becomes easier to understand how victims internalize responsibility, leading to long-term feelings of guilt and inadequacy,” she explains.

For this reason, she believes that the finding that 84 percent of victims blame themselves underscores the urgent need to change the public discourse and clearly assign responsibility for violence solely to perpetrators, without any relativization.

Is legislation part of the problem?

Hrnjak also points out that many forms of digital violence in Serbia are not clearly recognized as criminal offenses, particularly those involving control, surveillance, revenge pornography, hate speech, or digital stalking.

“Even when certain forms are recognized, the burden is often placed on the victim to collect evidence, confront the perpetrator, cover legal costs, and carry the weight of the process. In practice, most cases are not prosecuted ex officio, and the message sent to victims is clear: ‘you are on your own.’ In such an environment, it is entirely expected that victims internalize guilt that in reality belongs to perpetrators,” she explains.

As a result, victims have little trust in institutions, which too often leave them without support, leading to extremely low reporting rates.

“Only three percent of victims of digital violence have contacted institutions, while 21 percent say they do not know whom to turn to at all. Almost half of the population (47 percent) believes that state institutions deal little or not at all with the problem of digital violence. In comparison, only 10 percent believe they address it to a considerable extent,” Hrnjak adds.

Digital violence is still not recognized as a distinct criminal offense under Serbia’s Criminal Code, although this may change with the announced amendments. Until that happens, Hrnjak warns, digital violence will remain a space of impunity, which is the strongest form of support for perpetrators.

Link to the N1 article: https://n1info.rs/vesti/digitalno-nasilje-i-zene-ko-je-kriv/

FACEBOOK

FACEBOOK TWITTER

TWITTER YOUTUBE

YOUTUBE